Early Education in Charleston (1895-1940s)

South Carolina’s 1895 constitution set up the state’s system of public schools. The constitution also required that public schools be segregated by race. Because white men controlled the money and the school boards, more money was spent on white schools than black schools. Even though the Supreme Court ruled that segregated facilities must be “separate but equal,” this was rarely put into practice.

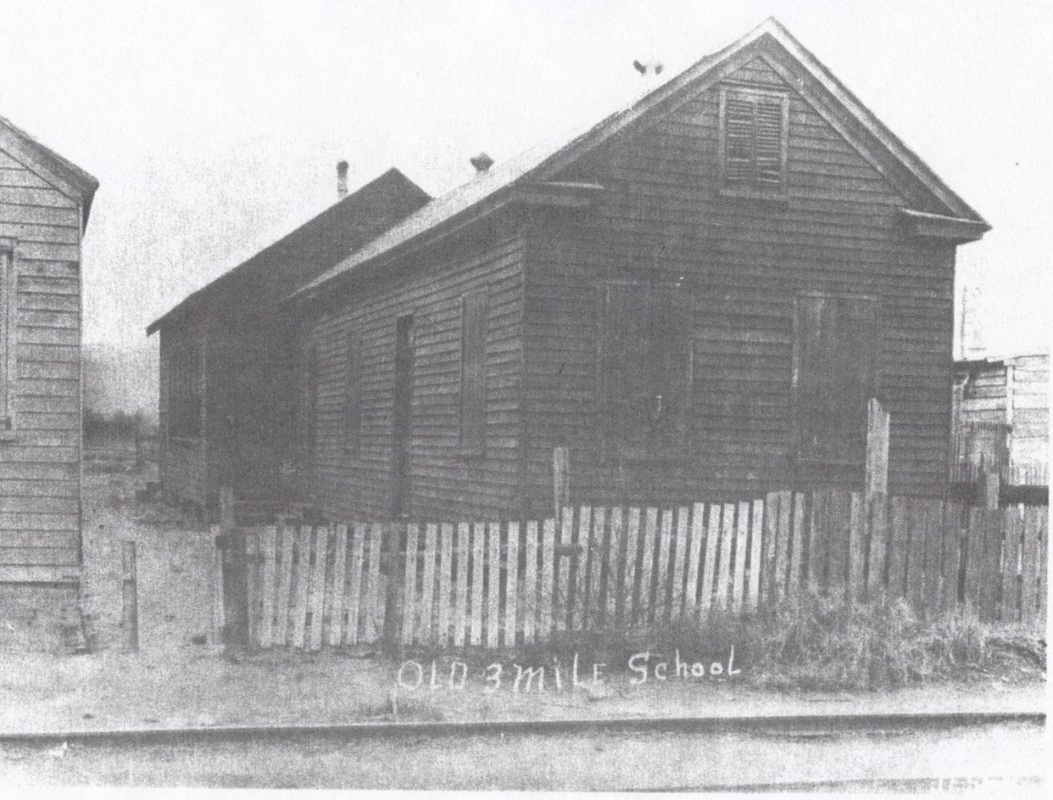

In 1913, South Carolina spent an average of $14.94 on each white student and only $1.86 for its black students. Many African American students attended school in barns, churches, or houses. If black students were lucky enough to have a school house, it was usually very small and in very poor shape.

South Carolina’s 1895 constitution set up the state’s system of public schools. The constitution also required that public schools be segregated by race. Because white men controlled the money and the school boards, more money was spent on white schools than black schools. Even though the Supreme Court ruled that segregated facilities must be “separate but equal,” this was rarely put into practice.

In 1913, South Carolina spent an average of $14.94 on each white student and only $1.86 for its black students. Many African American students attended school in barns, churches, or houses. If black students were lucky enough to have a school house, it was usually very small and in very poor shape.

|

Charleston County also had a sharp divide between rural and city schools in addition to black and white schools. Rural African American students attended school with only one or two teachers. The schools on the peninsula were larger.

There were few high schools for black students in the early twentieth century. The first black high schools in Charleston were opened as religious schools. These schools included Laing School in Mt. Pleasant, Avery Normal School in Charleston (both of which opened shortly after the end of the Civil War), and Immaculate Conception School in Charleston, opened in 1903 by the Sisters of Our Lady of Mercy. “[The students] had to walk long distances, and then, when they got to school, they would be cold unless they gathered the wood to put in the pot-belly stove….they had no desks at first. They would kneel on the floor and use the benches to write on, or else bend over and work in their laps.” --Mamie Garvin Fields, a teacher at a small school on James Island in the 1920s. The buildings of Avery Normal Institute (125 Bull Street, Charleston) and Immaculate Conception School (200 Coming Street, Charleston) still exist. Avery Normal Institute is owned by the College of Charleston and is open for tours.

|

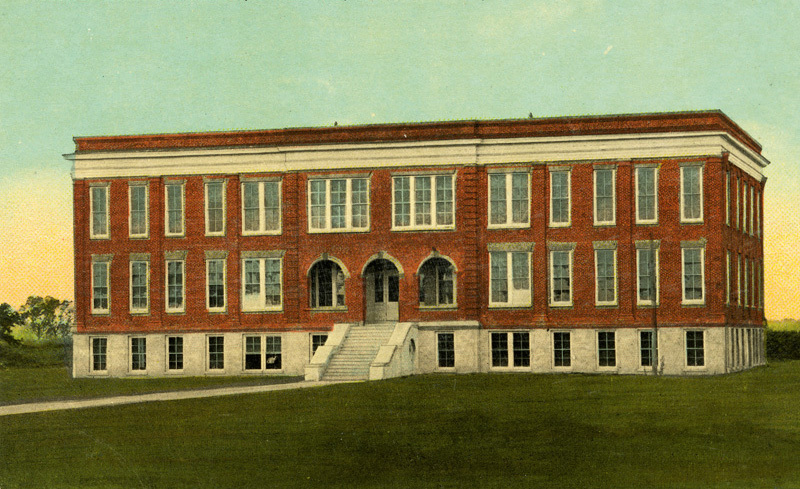

Charleston did not have a publically-funded high school until 1911, when the school district agreed to administer Charleston Industrial School, a free school for blacks previously operated with donations and grants. The school district constructed a new school building for Charleston Industrial School on President Street. Charleston Industrial School became Burke Industrial School in 1921.

Privately-owned Laing School in Mt. Pleasant became a public high school in the 1930s. There was no transportation or buses for black children. Students recall old textbooks with missing pages and asking their parents to pay for hand-me-down books. Schools were overcrowded and many had to have double shifts at the schools, with some children attending school from 7:00am to 2:00pm and other children attending school from 2:00pm to 7:00pm. In 1949, Charleston County had three black high schools and seven white high schools. No black high schools were located in North Charleston, McClellanville, or on the Sea Islands. However, African American parents that were able sent their students to school in Charleston and Mt. Pleasant worked hard to pay for tuition, room, and board. |