Briggs v. Elliott (1947-1951)

The advent of World War II brought the nation, and Charleston County, out of the Great Depression. War spending improved the economy, especially in North Charleston as the Charleston Navy Base expanded at a rapid rate. African Americans moved to the city from the farms to take advantage of the improved economy. This led to even more overcrowding in Charleston County’s black schools. The condition of the school buildings themselves continued to deteriorate. Statewide, by 1948, the value of South Carolina’s black schools was $12.9 million compared to white schools at $68.4 million.

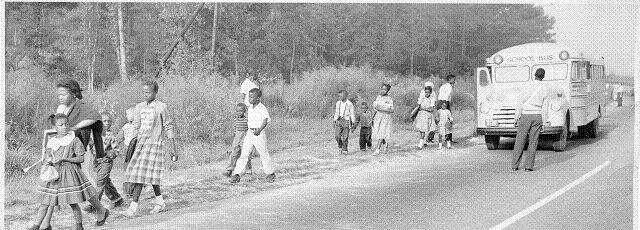

In Clarendon County, about 65 miles north of Charleston, African American parents were fed up with the lack of transportation for their children, the poor school facilities, and the poor leadership in black schools in the county. The parents decided to sue the school district, starting first with the issue of transportation. The South Carolina National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) supported the parents in their lawsuit.

The advent of World War II brought the nation, and Charleston County, out of the Great Depression. War spending improved the economy, especially in North Charleston as the Charleston Navy Base expanded at a rapid rate. African Americans moved to the city from the farms to take advantage of the improved economy. This led to even more overcrowding in Charleston County’s black schools. The condition of the school buildings themselves continued to deteriorate. Statewide, by 1948, the value of South Carolina’s black schools was $12.9 million compared to white schools at $68.4 million.

In Clarendon County, about 65 miles north of Charleston, African American parents were fed up with the lack of transportation for their children, the poor school facilities, and the poor leadership in black schools in the county. The parents decided to sue the school district, starting first with the issue of transportation. The South Carolina National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) supported the parents in their lawsuit.

Although the suit to get a bus for transportation for African American students ultimately failed, the Clarendon parents regrouped and got the attention of the national NAACP organization. Thurgood Marshall, the NAACP’s lawyer, assisted the Clarendon parents in filing a lawsuit calling for the equalization of school facilities and education in the school district. This petition became known as Briggs v. Elliott (click here to read a copy of the petition).

South Carolina’s governor James Byrnes learned of the petition and decided to take action to equalize white and black schools, declaring:

“We should provide [equal schools] because it is right and not wait until we are forced by the United States courts to

provide them.”

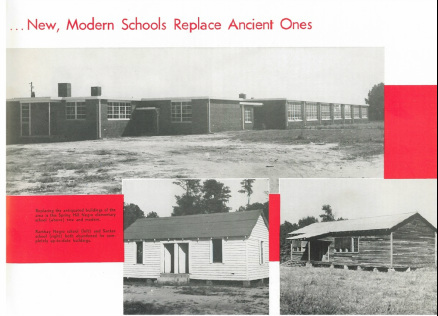

Governor Byrnes led South Carolina’s General Assembly in passing the state’s first sales tax of 3% to fund needed improvements to schools. The state took over school transportation and purchased buses to transport both white and black students to school. The state also required school districts to close most of their small schools and build new larger ones for students.

South Carolina’s governor James Byrnes learned of the petition and decided to take action to equalize white and black schools, declaring:

“We should provide [equal schools] because it is right and not wait until we are forced by the United States courts to

provide them.”

Governor Byrnes led South Carolina’s General Assembly in passing the state’s first sales tax of 3% to fund needed improvements to schools. The state took over school transportation and purchased buses to transport both white and black students to school. The state also required school districts to close most of their small schools and build new larger ones for students.

With new tax money in hand, the Clarendon County school district began construction on a new black high school building. However, the NAACP decided to change its strategy in Briggs v. Elliott, making the lawsuit the nation’s first calling for the desegregation of public schools, arguing that segregation created inequality and that “separate” could never be “equal.” The case was heard in 1951 in the US District Court building in Charleston.

The US District Court ruled against the NAACP and the Clarendon parents in their Briggs decision. Two of the judges believed that the state should be given time to implement its equalization program. One judge, J. Waties Waring, dissented from the majority opinion, stating that “segregation is per se, unequal.” It was the first

time a judge in a Southern state ruled against legal segregation. The NAACP appealed the Briggs decision to the US Supreme Court, where it joined similar cases to be tried in Brown v. Board of Education.

Learn more about Equalization in Charleston (1951-1962)

The US District Court ruled against the NAACP and the Clarendon parents in their Briggs decision. Two of the judges believed that the state should be given time to implement its equalization program. One judge, J. Waties Waring, dissented from the majority opinion, stating that “segregation is per se, unequal.” It was the first

time a judge in a Southern state ruled against legal segregation. The NAACP appealed the Briggs decision to the US Supreme Court, where it joined similar cases to be tried in Brown v. Board of Education.

Learn more about Equalization in Charleston (1951-1962)