After Equalization

Although the majority of South Carolina’s equalization funds were expended by 1955, the equalization program continued to fund new schools and renovations and additions to existing schools. Governor James Byrnes temporarily suspended the equalization program in the wake of the Brown v. Board of Education decision in 1954, but after consultation with white and black leaders across the state, decided to reinstate the program.

Despite the Supreme Court’s order to desegregate schools “with all deliberate speed” in Clarendon County, South Carolina’s school officials and state politicians avoided any desegregation of the public school system until 1963. In January 1963, Harvey Gantt desegregated Clemson University, and in September 1963, eleven African American students desegregated the Charleston County public schools. Other school districts followed suit, allowing at minimum, a token desegregation with a handful of black students in white schools. Rarely did white students desegregate black schools.

Parents and other community leaders responded to school desegregation by creating private schools that could discriminate in accepting applications to attend. Prior to 1956, South Carolina had only 16 private schools. Between 1963 and 1975, almost 200 new private schools were created in the state. In some of the more rural, majority-African American counties in South Carolina, these schools enrolled over 90% of the white children in the public school system. Named “segregation academies,” these private schools continued segregation in education throughout South Carolina. In Clarendon County today, Summerton High School has an enrollment of 95% African American students, while the whites attend Clarendon Hall. Clarendon Hall only began accepting African American students in 2000.

A new website is dedicated to collecting and telling the stories of these segregation schools. Visit https://www.theacademystories.com for stories and histories from across the South.

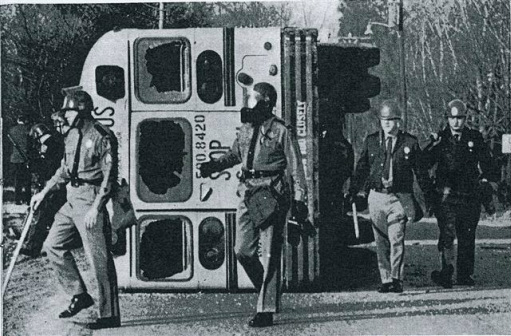

The federal government forced South Carolina to dismantle its dual school system, where certain schools were predominately black or white, by the beginning of the 1970-1971 school year. Greenville and Darlington counties, under specific court cases, had to integrate their schools by the end of the 1969-1970 school system. This order led to protests and violence in Lamar, where a group of almost 200 white adults attacked and overturned a school bus full of black children. Over three thousand of Darlington County’s white students had boycotted school for weeks before the mob attack.

sThe dismantling of the dual school system affected black schools, even those recently built as part of the equalization program. School districts often chose to close black high schools or change the high schools to elementary or junior high schools in the new system. These changes, especially in black high schools, led to resentment among students and the communities, as mascots, school colors, and sports were often changed in favor of the historically white school’s mascots or were changed completely for the new school. Many black schools across the state were closed in 1970 or shortly thereafter.

For more information on South Carolina’s struggles to integrate its schools, see these sources:

Edgar, Walter B. South Carolina in the Modern Age. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1992.

"Hidden Figures Revealed." The Johnsonian (April 17, 2019). Available online at http://mytjnow.com/2019/04/17/hidden-figures-revealed/

Monk, John. "After 50 Years, SC White Supremacist School Bus Riot Still Haunts Survivors." The State (8 March 2020). Available online at: https://www.thestate.com/news/politics-government/article240897681.html

Montgomery, Warner M. Columbia Schools: A History of Richland County School District One, Columbia, South Carolina, 1792-2000. Columbia, SC:

Warner M. Montgomery, 2002. (This book has a very detailed and excellent account of the integration of the dual school systems in Columbia.)

“Private Schools: The Last Refuge.” Time (November 14, 1969). PDF here.

Truitt, Thomas E. Brick Walls: Reflections on Race in a Southern School District. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006.

For more information on South Carolina’s struggles to integrate its schools, see these sources:

Edgar, Walter B. South Carolina in the Modern Age. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 1992.

"Hidden Figures Revealed." The Johnsonian (April 17, 2019). Available online at http://mytjnow.com/2019/04/17/hidden-figures-revealed/

Monk, John. "After 50 Years, SC White Supremacist School Bus Riot Still Haunts Survivors." The State (8 March 2020). Available online at: https://www.thestate.com/news/politics-government/article240897681.html

Montgomery, Warner M. Columbia Schools: A History of Richland County School District One, Columbia, South Carolina, 1792-2000. Columbia, SC:

Warner M. Montgomery, 2002. (This book has a very detailed and excellent account of the integration of the dual school systems in Columbia.)

“Private Schools: The Last Refuge.” Time (November 14, 1969). PDF here.

Truitt, Thomas E. Brick Walls: Reflections on Race in a Southern School District. Columbia: University of South Carolina Press, 2006.